Guest commentary: List the tope shark under Endangered Species Act - La Jolla Light

The conservation organizations Defend Them All Foundation and the Center for Biological Diversity have submitted a petition to the National Marine Fisheries Service requesting protection of the tope shark (Galeorhinus galeus) under the U.S. Endangered Species Act, including the designation of critical habitat for the species in U.S. waters.

West Coast breeding sites such as La Jolla are essential to the survival and recovery of the tope shark due to the species' tendency to occupy warmer waters to incubate their embryos to minimize the sharks' 12-month gestation period. Studies suggest that pups remain in their nursery grounds for up to two years.

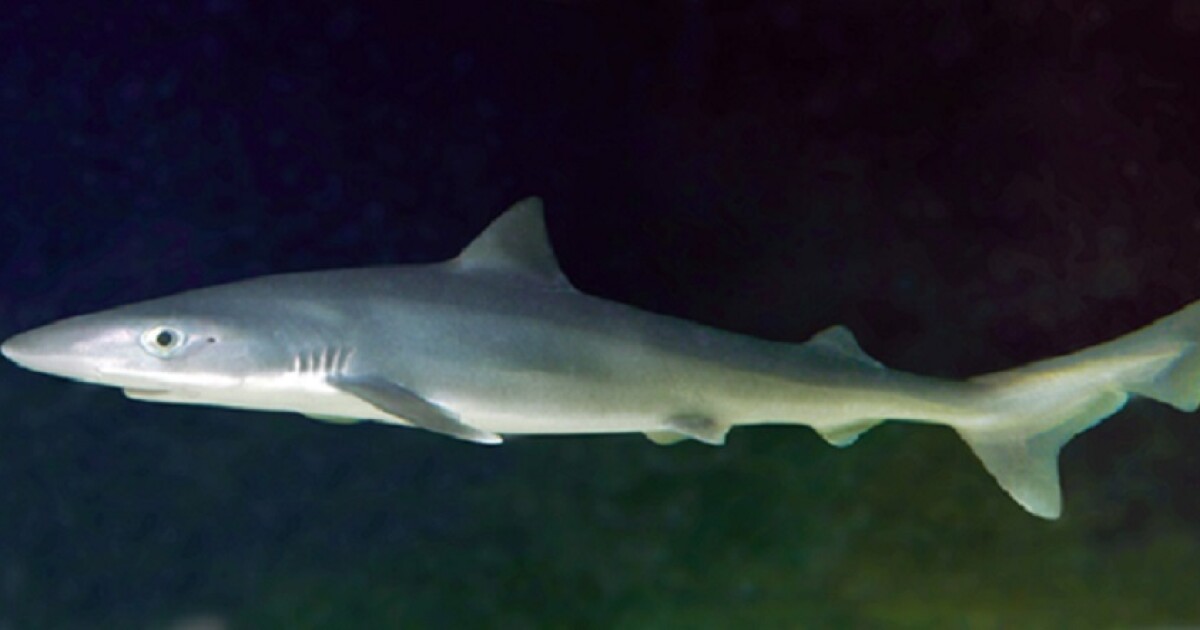

The tope shark, also known as the soupfin shark, is long and slender, grows up to 6½ feet long and nearly 100 pounds, has a late sexual maturity of approximately 12½ years and lives up to 60 years. Tope sharks are known for far-ranging seasonal migrations that cross multiple state and/or national borders.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature has categorized the tope shark as critically endangered due to a steep 88 percent decline in the species' global population over the past 79 years, primarily due to overfishing. The sharks' slow maturation rate and tendency to swim in schools segregated by sex and age make them susceptible to overexploitation, as multiple sharks in the same school can be caught simultaneously, often inhibiting breeding by removing the species' reproductive members. For example, most tope sharks found in Southern California are females, while males predominate from Northern California to British Columbia.

While fishing pressures and accidental capture as bycatch are the primary threats to the species, habitat degradation, climate change and inadequate regulatory mechanisms are further factors driving the species to extinction.

Fishing and bycatch

Despite a clear international consensus that sharks should be protected globally, sharks — including the tope shark — continue to be exploited into extinction.

Tope historically have been harvested for squalene, a lipid in shark livers. While an abundance of plant-based and synthetic alternatives exist, shark-derived liver oil remains in high demand for use in cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, dietary supplements, sunscreens and biofuels.

Sportfishing of tope is still authorized, and commercial trade of whole tope sharks is often permitted by direct fishing or as a bycatch product. Tope are being targeted directly in fisheries but also are particularly vulnerable to incidental capture as bycatch in pelagic gillnet and long-line fisheries, as well as trawl, hook-and-line, troll lines, trammel nets and traps due to their preference for teleost fish and tendency to swim in schools.

Bycatch animals become entangled in this mesh around their necks, mouths and flippers, which prevents proper feeding, constricts growth, causes infection or leads to extreme fatigue.

Both targeted and incidental capture are more likely to occur in bays and estuaries, where pregnant females are known to seek refuge to give birth.

Habitat degradation

As top predators in the food chain, sharks are prone to the accumulation of high levels of toxic pollutants. Considering the tope sharks' reliance on near-shore breeding areas, toxicants pose serious threats to the tope shark throughout its range, and in California in particular, given excessive levels of DDT — a synthetic insecticide — in and around important habitats. DDT was developed in the 1940s to combat disease in military and civilian populations and control insects in crop and livestock production. [Because of health and environmental effects and its persistence in the environment, DDT's agricultural use in the United States was banned in 1972, and a worldwide ban on its agricultural use has been in effect since 2004.]

Many marine species continue to be harmed by the legacy of DDT contamination. In sharks, compounds like DDT are stored in the liver and passed from mother to her pups, leaving the pups plagued with DDT poisoning.

In light of research on similar species, exposure to and bioaccumulation of DDT and other pollutants likely have played a role in the tope shark's decline. Studies have revealed elevated levels of both inorganic and organic micropollutants in sharks' muscles and liver, including heavy metals (e.g., mercury, cadmium, arsenic, lead) and various persistent organic pollutants.

Climate change and coastal development

Climate change and coastal development are especially harmful to tope given the species' dependence on shallow warm areas for gestation pup rearing and juvenile development for up to two years.

Sharks are highly likely to shift their distribution or expand into new habitats to follow preferable ocean conditions due to climate change. The effects of climate will lead to significant changes in phytoplankton — the foundation of the marine food web — biomass and shifts in species dominance. Declines in phytoplankton will likely affect secondary and tertiary-level consumers such as fish and sharks.

Rising temperatures, which mainly impact the ocean, go far beyond death, extinctions and habitat loss. Instead, rising temperatures alter fundamental processes, leading to reorganization and ecological surprises. In effect, the loss of sharks likely would be catastrophic to marine ecosystems. Ocean change also will increase ocean acidification, stratification and dead zones.

The need for listing as endangered

Current conservation regulations are ineffective to ensure the survival of the tope shark. This is illustrated by the few conservation measures present throughout the tope shark's global range, despite growing international awareness of threats to the species.

The listing of the tope shark as endangered under the U.S. Endangered Species Act and designation of critical habitat for the species within U.S. waters would significantly improve the species' chances of survival by curtailing habitat destruction, reducing unsustainable harvest and other man-made factors, and strengthening regulatory mechanisms.

The Defend Them All Foundation and the Center for Biological Diversity hope that through this listing, the tope shark population will stabilize and increase off the West Coast.

Hunter Collins is a law student at the University of San Diego and an associate at the Defend Them All Foundation. ◆

Comments

Post a Comment