Longhorn Nights - D Magazine

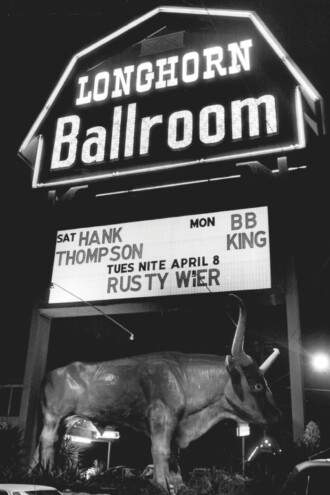

The iconic 72-year-old Longhorn Ballroom sits on an unattractive stretch of South Riverfront Boulevard where the Trinity River levees give way to the forest, south of downtown. Neighboring businesses are a scrap metal yard and a used-tire shop.

I hadn't seen the inside for many years, until, in November, I joined six dozen or so others for a tour led by outsize music impresario Edwin Cabaniss of Kessler Theater renown. Cabaniss had plans to renovate the 4-acre complex, adding an outdoor music venue. (Months later, the Dallas Plan Commission gave its stamp of approval, sending the proposed project on to the full City Council, which is where the project sits to this day.) With self-assurance and good humor, Cabaniss talked about the Longhorn's history and bringing back to life the civic jewel with its jagged karma. In the swallowing emptiness of the cavernous building, we envisioned a new day for arguably the most important music venue in Texas. Absent chairs and tables, music and color, I sensed the ghosts of the old days, memories of quirky characters and twisted tales, some of which I myself participated in and can share without fear of either ending a marriage or providing fodder for a grand jury.

It's hard to get your head around the full history of the Longhorn. Dallas millionaire O.L. Nelms built the place in 1950, when it was called Bob Wills' Ranch House. The Western swing king and fiddling legend rode his horse, Punkin, on the big dance floor with rubber-shod hooves. A 45-foot bar was inlaid with 1,700 silver dollars. But the extravagant club faced financial ruin in less than two years. Wills ran the place on the level, but the bookkeeper and others were crooked as snakes.

"Bob was paying the taxes to his bookkeeper, but he [the bookkeeper] wasn't paying Uncle [Sam]." That comes from a handwritten history of the Longhorn that a man named Dewey Groom gave me in 1977. I discovered it not long ago in a forgotten drawer at my house, and it spurred me to begin collecting oral histories of the place for a book (43 people so far).

Dewey leased the space from Nelms in 1958, opening the Longhorn Ranch, which he later changed to the Longhorn Ballroom. "I had a very hard time keeping the club open," Dewey wrote, "but thanks to my thousands of friends and fans, I made it through some stormy weather."

Into the mid-1970s Groom's Longhorn Band played Bob Wills-style Western swing with a 12-piece band, and many of Wills' old Texas Playboys were part of it. But the music was evolving. Dewey had billed the club as "the nation's most unique ballroom." In addition to regular dancing crowds and weekend star artists, it hosted live radio simulcasts, recording sessions (from Merle Haggard to R&B's Johnnie Taylor), and special occasions such as in 1978 when NBC used it as the setting to broadcast Fifty Years of Country Music with Loretta Lynn and Johnny Cash. Longhorn favorite Ernest Tubb recorded his Live New Year's Eve 1979 there.

The club would close Monday nights, and Dewey leased it (but sold beer and setups) to the crowds that came for "Black night." That was the one day of the week the country clubs and restaurants were closed and their Black employees had a day off. Bobby Rush, an R&B artist who worked the Chitlin' Circuit throughout Texas and the South, first appeared at the Longhorn in 1966. He put it this way to me: "You couldn't book the Longhorn if you couldn't pack the Longhorn. It was like playing Carnegie Hall."

Dallas soul and R&B promoters (John Henry and Howard Branch, then Al Wash and Dwaine Caraway) filled the house, covering the huge dance floor with extra tables. Those nights showcased Bobby Rush, Ray Charles, B.B. King, Bobby "Blue" Bland, Millie Jackson, James Brown, Al Green, Johnnie Taylor (who often asked local blues favorite R.L. Griffin and his band to open for him), Otis Redding, and Little Milton, to name a few. (The great Duke Ellington played there in 1951 when it was Bob Wills' Ranch House, and Nat King Cole played it in 1954.)

Along the way, Dewey added massive air conditioning to handle the cigarette smoke problem. The Longhorn Ballroom, only 35 feet shorter than a football field, was Texas kitsch grandeur with 18 large wagon wheel chandeliers and giant pastel green faux cactus support beams. Wall-length murals of Longhorn cattle drives depicted dashing horseback cowboys in pursuit over landscapes that tried for 3D but didn't quite succeed.

Mostly middle-aged, big-haired hostesses met you at the door outfitted in short, flouncy cowgirl skirts, fringed vests, red kerchiefs, and white boots. They called you "doorlin' " and ushered you with flashlights through the marvelous cool darkness to your table with its red-checked tablecloth and saloon chairs. With the best country music house band in the state, the feel was exotic in a manner unmatched. The Longhorn was a dance experience but not a honky-tonk. Janet McBride, Dewey's female vocalist and record company administrator in the 1960s, told me: "Dewey wouldn't let you say 'honky-tonk.' "

Dewey finally bought the place from Nelms for $350,000, and the new and improved ballroom opened in 1968, with Ray Price and his Cherokee Cowboys. That same year, the giant fiberglass steer (built in Minneapolis) went up under a barn-shaped sign presiding over the marquee. The steer measured 14 feet by 21 feet, with an 18-foot horn spread.

Dewey Groom's Longhorn Ballroom made music and Dallas history until the last night, New Year's Eve 1985. He brought out his dormant Longhorn Records label, and the band recorded a new souvenir song that frontman Curt Ryle had penned based on Bob Wills' "Faded Love" anthem, titled "Who'll Sing Faded Love (When Dewey and the Longhorn Band Is Gone)." The answer hangs in the ether.

After Dewey's long run on the sunny side, the club appeared to revert to its curse, earned since the Wills debacle, as a "pink elephant" (likely he meant white). Dewey wrote the phrase in his history, explaining his risk in 1958 when he took over the Longhorn. Younger guys bought and lost at the Longhorn. Ira Zack, who also owned the Belle Starr, committed suicide while running the Longhorn. Raul Ramirez, a former Dewey tenant (Raul's Cantina) across the parking lot, brought in the Hispanic songstress Selena and occasional concerts. Fred Alford of the Dallas Refrigerated Warehouse Co. gave it a try. Jay LaFrance bought it, made upgrades all around, and promoted it as an event space. He triumphed for a while and even won an award from Preservation Dallas. Still, the ballroom fell into bankruptcy.

That public gathering with Cabaniss in the empty Longhorn shell summoned a glimpse of future glory and, for me, the looming spectral presence of Doug Groom, Dewey's oldest son and my boyhood friend, who was bartender, soundboard troubleshooter, and talent booker. Doug had been a drummer briefly with the house band but quit since it played one too many waltzes for his rock-and-roll taste. A wisecracking party boy on his own beat, Doug had long hair and a beard that flouted Dewey's employee rules. Doug generally did what he wanted.

Mick Jagger's people called and said he wanted to come see Bobby Bland.

On the back of Doug's wide tooled leather belt, where you'd expect Buck or Leon or Jesse Ray, blocky letters spelled out FUCK ME. It was quite the conversation piece. Doug was one-dimensional that way (before wedding his second wife, the beautiful Judy Kreck Groom): if not searching for a woman and advertising it, he wanted to party and play guitar, all night, all of the time. It was the 1970s, and we were in our 20s.

Doug's died-and-gone-to-heaven moment came on one of the Longhorn's "Black nights." Working the sound system, he invited me down because Mick Jagger's people had called and said that Jagger, in town visiting Mesquite model Jerry Hall, wanted to come see Bobby "Blue" Bland. I called bullshit on Doug's fevered dream and didn't go. Jagger did arrive, though, and when he was about to leave, Doug brought him to Dewey's empty back office to drink Jose Cuervo tequila and snort cocaine.

Photographic proof exists of the drinking part, and Doug, remarkably alert, sits beside Mick, his arm draped over his new best friend's shoulder and a priceless, pinch-me grin on his face.

At some point Doug's hardworking little sister, Saran, dashed back to the office to get change for the bar. "It seemed like Mick was all dressed up in white," she remembers. "I didn't know who he was, and Doug says, 'Aren't you going to say anything? Don't you know who this is?' I said no. Doug says, 'This is Mick Jagger,' and I said, 'It's nice to meet you, sir. How are you. Any kin to Ronny?' " Ronny Jagger was Saran's insurance agent.

Dewey's die-hard fans loved the Sunday matinee, 2 to 11 pm. His welcoming stage presence always warmed his crowd. "He would go into another gear and make sure to mention so-and-so's name over the PA system and make her feel special," says Junior Knight, who played pedal steel in the band. "He was all about the people."

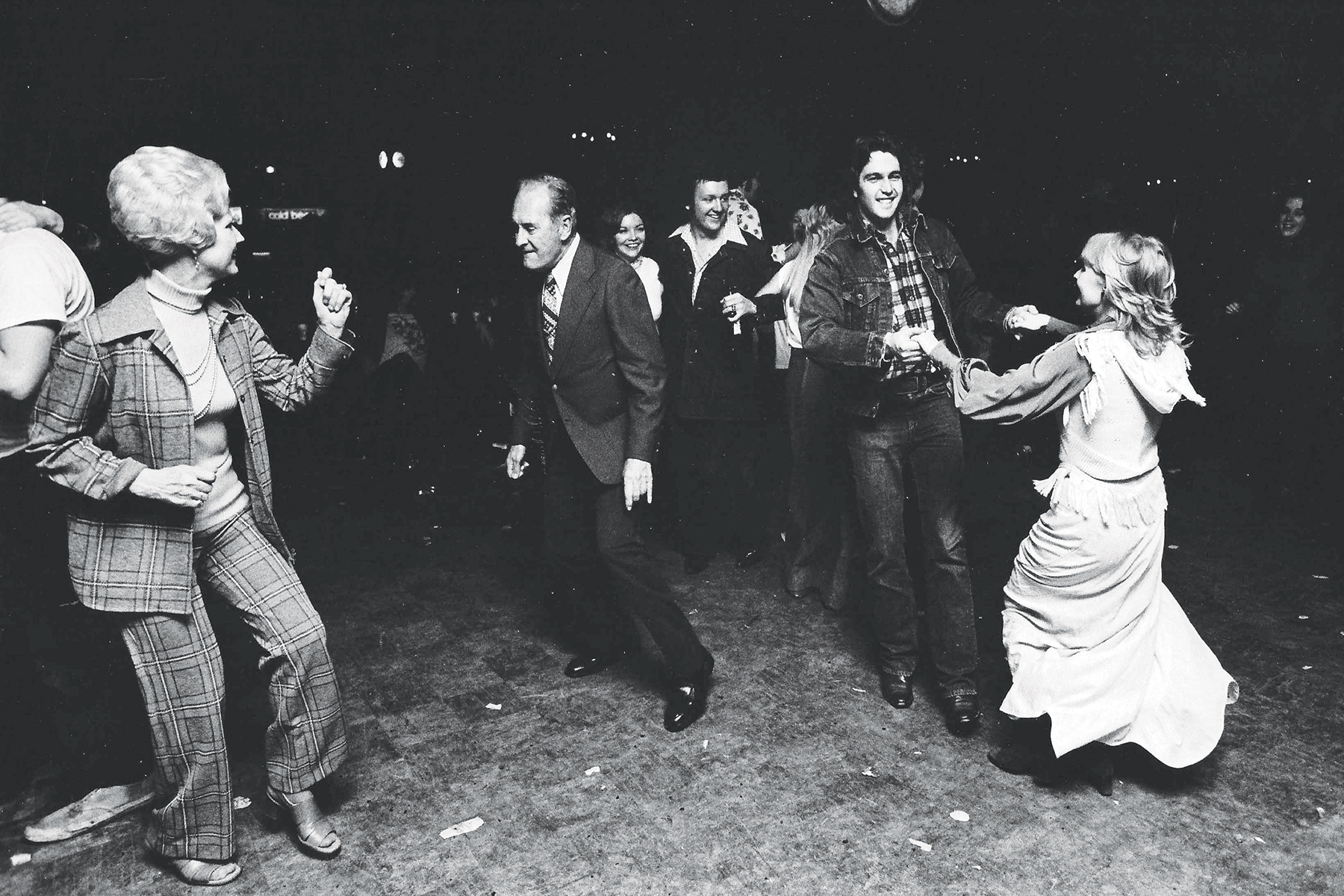

Invariably those people were treated to the Ray Price shuffles—"Crazy Arms," "Release Me," "Heartaches by the Number"—and Bob Wills' venerable "Faded Love." The true believers—dancers for years, surrounded by their pals—couldn't get enough. Sundays were a time for older dancers and the widowed women who had outdistanced their husbands in the mortality race. They would come and dance or maybe just sit and savor the music's hold on who they were and would always be.

Cradled in this cozy moment, more than a few times some geriatric heart beat its last. "There's no telling how many loyal customers passed away, literally died, in the club," Knight says. "We'd be playing and Dewey would be onstage or out milling in the crowd, and somebody would die. They'd call the paramedics to come attend to them wherever they were, on the dance floor or over by the tables. Dewey made us kind of bring the music down where you could barely hear us, but we'd keep on playing. You didn't stop the show unless it was right on the dance floor."

By the mid-1970s Dewey was a celebrity in Dallas entertainment, riding the bucking bronco of customer approval at the club by never leaving it. The venue was famous because of Dewey in his Western leisure suit, his wide face framed by jet black hair combed back, and his baritone sound all growled up and seasoned over Weller whiskey, a voice that could seem menacing if it weren't coming from Dewey. "I love people, and they love me," he said many times, beaming. And it was so.

Known as Daddy Dewey, he helped plenty of musicians on the way up. Willie Nelson and his band, Hank Thompson, Boxcar Willie, Bill Mack, and Chill Wills all came for his 25th anniversary in the business, in 1975. I functioned as Dewey's aide-de-camp that weekend, which meant shepherding vodka-swilling Chill Wills. When Willie went on break, Chill instinctively found the stage. Too tippled to muster his trademark "Howdy, cuzin," he stood silent, staring before the footlights like a cow watching a magic trick, while people applauded the cozy cowboy sidekick role he'd played for decades.

Gently, I led him off the stage as he demanded more booze. I walked him back to Willie's bus to join Dewey, then stood sentinel at the door. After that, Dewey gave me the club owner solution for Chill's big thirst: "Fill it with water and tell him it's vodka."

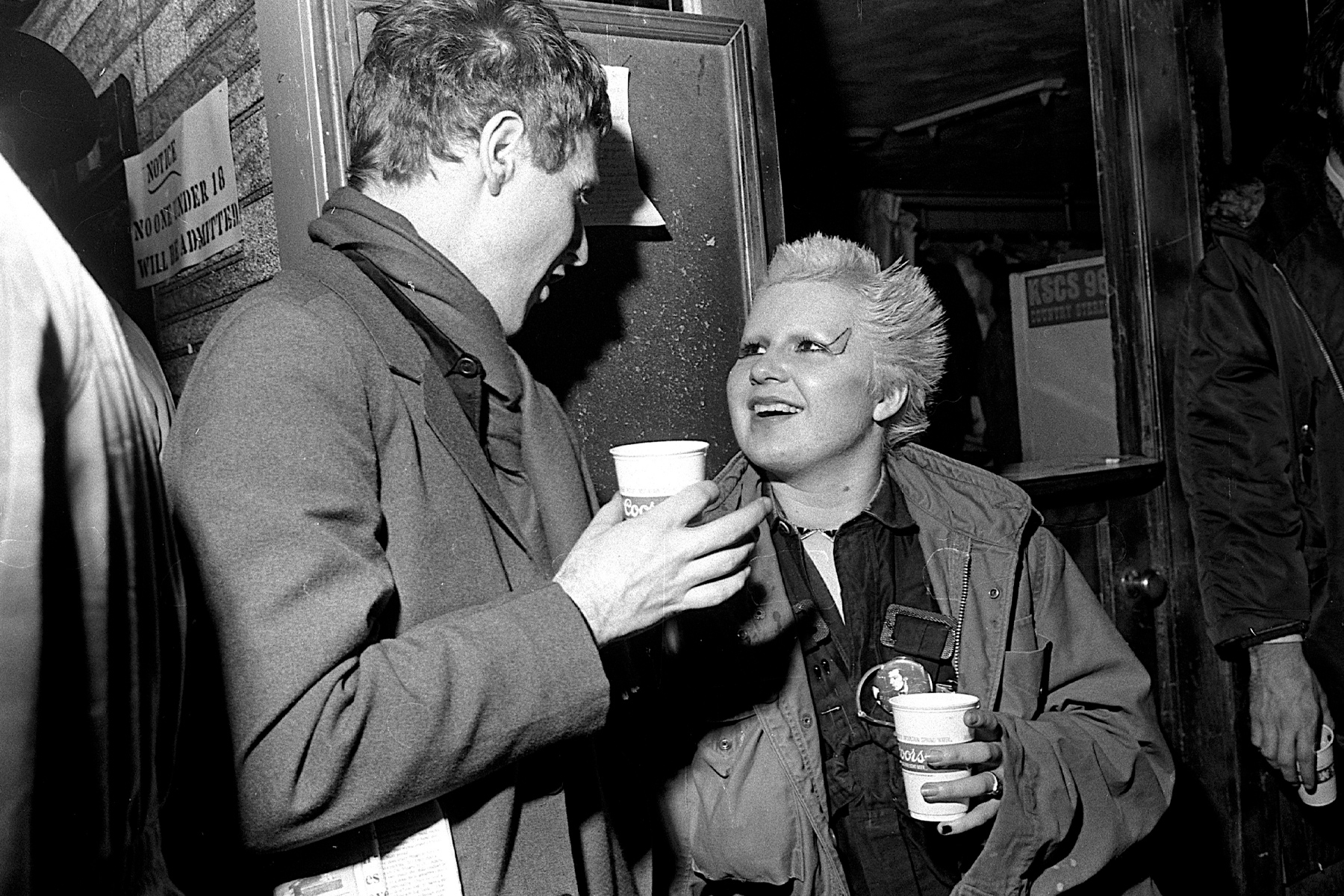

By all accounts, the Sex Pistols booking was a fluke. Stone City Attractions wanted January 10, 1978, a Tuesday, one of the nights the Longhorn was closed. The Grooms had a big Merle Haggard show coming and wanted the time off. "Doug was like, 'Man, I don't want to do it,' and Dad didn't really want to do it, either," Saran says. (Dewey's daughter worked nights at the club's cashier window and had wed Junior Knight at the employee Christmas party.) "And one of them said, 'Just haul off and charge them some crazy-ass money, and they'll turn it down.' It was considerable, like twice the normal rate. They didn't blink, said, 'Fine, we'll take it.' " So the Grooms cinched down their belts, decided to sell beer only in paper cups (a Longhorn first), and tried to ignore phoned-in rumors of an assassination attempt on the lead singer.

Subsequent world press coverage (Annie Leibovitz had her camera stolen) reported that a woman had punched Sid Vicious onstage and that blood covered his face and shirtless chest. (Others reported that someone had thrown a beer can at him, or that he had hit his face on a microphone. All three could be true.) The scene smacked of the wrestling that was staged around the corner on Industrial Boulevard at the Sportatorium.

Les Fincher, a New York photographer and Pleasant Grove friend of mine from school days, was in town and popped in early to visit with Doug and see the Sex Pistols. He left with frames of a short blond woman, pre-show, chatting up Malcolm McLaren, a PR genius and the Sex Pistols' manager. Later images showed it was the same woman who may have attacked Sid onstage.

On a slow night, Doug would call you away from what you thought was important and present compelling logic over any objections. I can hear him: "Who cares if you don't like the band? There's women, cold beer, and I get you in free. Are you stupid or what?" The Longhorn was a beacon for Doug's friends from Pleasant Grove and the Abby Inn Bar in Northeast Dallas; they were a sort of posse and primed for foolishness like his GFR (Grand Fucking Reunion) birthday excesses in the smaller partitioned section where Nelms had created his Guthrie Club. A fine but calm enough madness prevailed, if you discount the mass mooning one year involving a photographer and 80 or so boys and girls.

At Doug's invitation, I believe I witnessed a record eight-cape performance as James Brown danced, sweated, and gyrated into a quivering kneel before cape man Danny Ray ministered to him and he arose, revived, the hardest-working man in show business.

Occasional weeknights, Doug and posse member Rick Roseman would close the club down, douse the lights, and listen for rats on the dance floor. Bunkered with pellet guns and .22-caliber rifles in a little window area for selling t-shirts, the hunters waited and drank more beer. Once he sensed a little army scurrying, Doug would turn on the lights, which froze the rodents until the first volley.

Through Doug I became friends with his sister, Saran, and brother, Richard, and also with Wilson "Willy" Wren, who, while not a family member, had risen from janitor to general manager. Fiddle player James Pennebaker, a former Longhorn Band member, remembered Willy's importance: "If it had not been for Willy and Quinlan [Dewey's wife], the wheels would have come off the club years before."

Willy bore a passing resemblance to country music superstar Charley Pride, who often appeared at the Longhorn. Dewey and Willy would walk across the parking lot to Raul's bar, where Dewey would order drinks for himself and "my friend Charley Pride."

Doug and I had been camping at Lake Texoma and were returning to Dallas on a Sunday. Doug said it was Dewey's birthday, and almost precisely at that moment I spied a roadside cardboard sign: "Nubian Kid Goats For Sale." And thus did the beautiful blue-eyed animal land in Doug's Chevy truck and even stayed put when we stopped at the store for another 12-pack.

I witnessed a record eight-cape performance by James Brown.

Headed down the road for the Longhorn's Sunday matinee, listening to Willie on KZEW-FM, we didn't think—I could stop right there—about how to give Dewey his gift.

Once on the premises, Doug snuck the goat into the wings backstage. Maybe we figured someone would see it and magically connect it to Dewey's birthday. With the band in toe-tapping stride, the goat began to pick its way from behind the bandstand, stumbling over mic cords and amp connections, and stuff started falling. The matinee diehards just roared. I never imagined it would be that funny.

I turned to confirm this wacky scene with Doug, but he had vanished. Dewey came off the stage and was headed toward me, talking really loudly about how he didn't like the goat AT ALL. I'd known Dewey for years but hadn't realized this large vein in his neck popped out when he yelled. Not sure what he was saying, but he was talking in the third person, like: "You don't do this to Dewey Groom!" By then I was staring down at my shoes, though, embarrassed that an OK idea had circled the drain into pranking jackassedry on my friend Dewey.

But Dewey now had himself a pet, and the goat lived with Dewey and Quinlan in Seagoville. Then the neighbor's Doberman grew up and cleared a fence and took down the beautiful blue-eyed Nubian that had once appeared onstage at the Longhorn Ballroom. Dewey buried it in his backyard and cried.

If Edwin Cabaniss commissions a new history of the Longhorn, I don't expect this story will make it. But it should.

This story originally appeared in the September issue of D Magazine. Write to [email protected].

Comments

Post a Comment